Want to Fix Medicaid? Look to Milton Friedman

The House of Representatives narrowly passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (HR 119) in dramatic fashion (215-214) last month. Most of the drama was on the Republican side. The House Freedom Caucus favored preserving the 2017 tax cuts but only if there were sufficient budget cuts to pay for it.

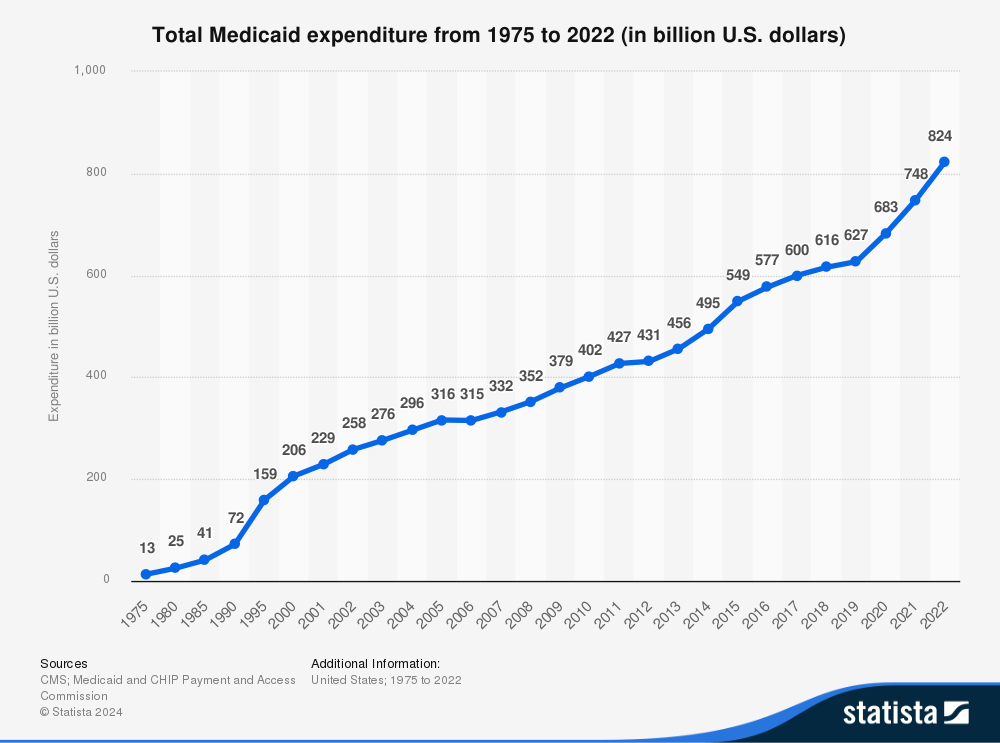

A central sticking point was Medicaid, both in terms of rules and in terms of funding. In the end, the cuts were larger than almost anyone expected, $880 billion over the next 10 years, and all but three House Freedom Caucus members voted yes. Every Democrat voted no.

The Obamacare “expansion” changed the original mission of Medicaid, which was to ensure the working poor and disabled didn’t end up without healthcare insurance. Medicaid had been, up until the Affordable Care Act of 2010, the default form of insurance for anyone who was poor or unable to work. Since then, even the young and perfectly able-bodied can qualify for Medicaid. Adding millions of newly eligible enrollees burned through money that could have been put toward elements of Medicaid’s original mission, things like investing in prenatal care for poor women.

Medicaid’s budget woes worsened with the onset of COVID-19. Spending increased even more rapidly, in part from the absence of normal coverage interruptions that were eliminated during COVID’s continuous enrollment provisions. At the same time, an aging population has led to rapidly rising long-term care costs among the poor elderly. Finally, a Byzantine system of below-market mandated reimbursement rates at the state level has become increasingly onerous to save money, especially in states with ballooning rolls like California, where Medicaid has been opened up to illegal aliens. Below-market mandated rates have caused price-shifting distortions to accumulate, and make the entire healthcare system less efficient.

Medicaid is an outstanding example of how not to structure a government program. Its daunting complexity results in people frequently migrating into and out of the program (this is especially problematic for programs that provide some kind of insurance because of adverse selection problems). Because it is fundamentally a government bureaucracy, problem-solving is mostly through top-down edicts or acts of Congress. In contrast, in many parts of American society entrepreneurs continuously adapt, adjust, and innovate to deal with new problems and to take advantage of new opportunities to improve service, reduce costs, or both.

The bill now faces an uncertain future in the Senate. Changes to Medicaid are going to produce a political backlash, even in some red states, since there will be political pressure for state governments to pick up the slack. But most importantly, a very large and dysfunctional system will remain intact and dysfunctional.

The problem with Medicaid goes far beyond Medicaid. In a rich society like ours, everyone is going to get a fair amount of healthcare one way or another. We are empathetic, sympathetic, interconnected, and rich, so most of us feel compelled to do something to help the uninsured and those without access to care. If a person is writhing in pain because he can’t get healthcare, most likely neither you nor anyone you know personally would just step over him without concern.

This is the real problem: healthcare in America has effectively become a non-excludable good. A non-excludable good is one we cannot keep others from consuming (e.g., national defense). Long ago, economists worked out why such goods are inevitably underprovided by the private market because of free riding. Since virtually everyone is going to get at least some healthcare when they need it, some take advantage of that by not buying their own health insurance.

Among the many economic challenges specific to healthcare markets, economists of all political stripes agree that this is the deepest problem. Recall that perhaps the biggest bone of contention with Obamacare was the individual mandate, put into the bill specifically to address the free rider problem. Many opposed the individual mandate for a variety of reasons, but did not challenge its premise, which was that there was a deep free rider problem to be dealt with in American healthcare.

The bold — but probably politically impossible — course of action would have been for House Republicans to eliminate the federal role in Medicaid. But if they are not going to return this issue, and its financing, to the states, then rather than further tweaking Medicaid and creating new problems, a better approach would be to find an alternative path to get government out of the business of healthcare for the poor. In short: provide basic healthcare insurance through vouchers.

To put it simply, eliminate Obamacare, Medicare, and Medicaid and replace them with a national healthcare voucher system. This transformative change for American healthcare could be limited to the level paid for with a national sales tax, and our unfunded liability problems would simply disappear. While, for practical reasons, this would likely have to start at the national level, the goal could be to then spin it off to the states.

Milton Friedman introduced the idea of using vouchers with respect to education 70 years ago. His ideas were summarily rejected as too naïve, too impractical, and even as irresponsible. Now we are in the midst of an explosion of school choice across the nation. How much better off would we be if we had listened to him long ago?

Friedman did not advocate using a voucher system for healthcare insurance. While his diagnosis of the problems confronting the American healthcare system was unimpeachable, he did not explicitly consider the problem of de facto non-excludability. Since this induces some citizens to save money by not buying healthcare insurance, it guarantees there will always be uninsured citizens. That, in turn, ultimately guarantees some level of government provision of either healthcare or healthcare insurance.

I believe that if he were alive today, Friedman would support vouchers for healthcare insurance. Vouchers provide the government with a means of funding a solution without having the government be the mechanism that provides the solution. As such, it mostly avoids the ever-growing creeping bureaucracies that suppress competition and introduce innumerable distortions and never-ending political opportunism.

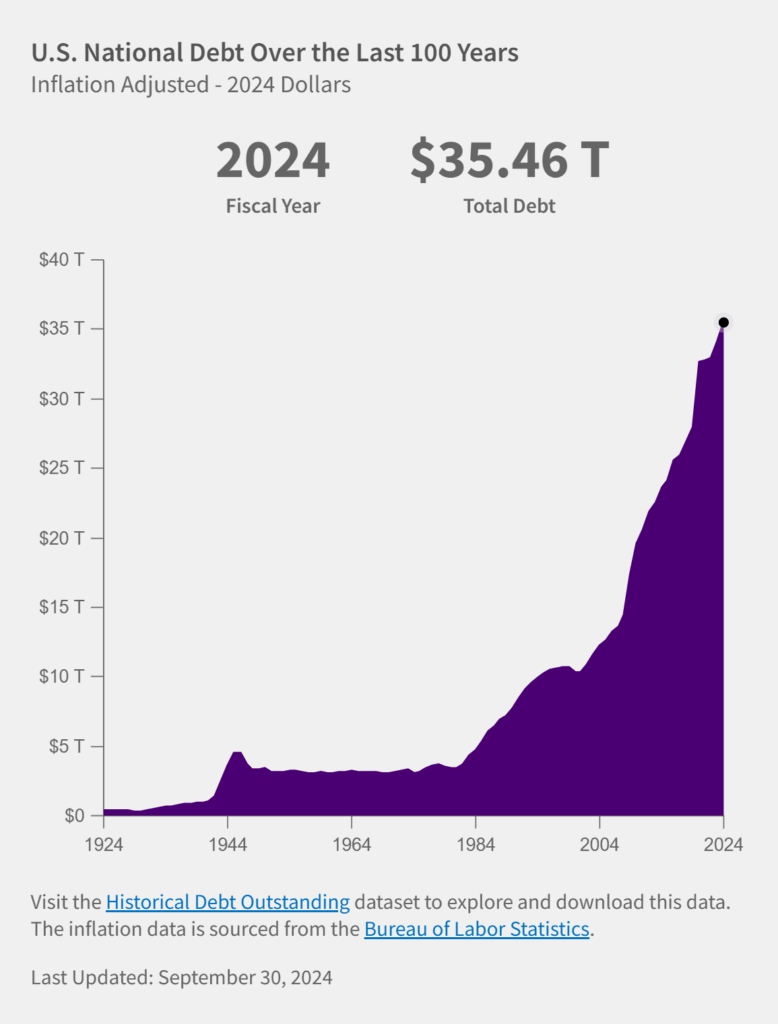

We can eliminate Medicaid, Medicare, and Obamacare by implementing a national voucher program for healthcare insurance for all citizens. By structuring the budget process to be self-balancing, we can ensure future generations are no longer saddled with a combination of increasing debt they never agreed to and lower quality of service than those who were responsible for that debt were able to enjoy.

Ever notice that when the topic is unfunded liabilities, Medicaid is rarely mentioned? Is that because Medicaid is on a healthy budget path? Hardly. Medicaid is not included in such conversations because Medicaid is not a self-funding program in the sense that it does not have its own dedicated payroll tax funding. At the federal level, it is funded out of the general budget.

If the federal budget were experiencing year-over-year surpluses, one could argue that it is not burdening future Americans because it is being cross-subsidized. But we are, in fact, experiencing year-over-year deficits, so any dollar the federal government spends on Medicaid is effectively a dollar of additional federal debt at the margin. Rising federal spending on Medicaid equals rising federal debt.

Far from a principled stand or a change in national direction, the latest Republican budget does little more than kick the can down the road — to avoid the political cost of actually doing what is best for the country.

How much more dysfunction and irresponsibility are we going to tolerate so we can pretend that our healthcare system is only for the deserving? We should be honest about the fact that we do, and will continue to, treat everyone. This is nothing to apologize for but it’s something we need to come to grips with.

A voucher program would redirect government power to unleash market competition among healthcare insurers and among healthcare providers. They will hate it. The NEA’s response to school vouchers should tell you everything you need to know.