Can a State Just Opt Out of Federal Social Security?

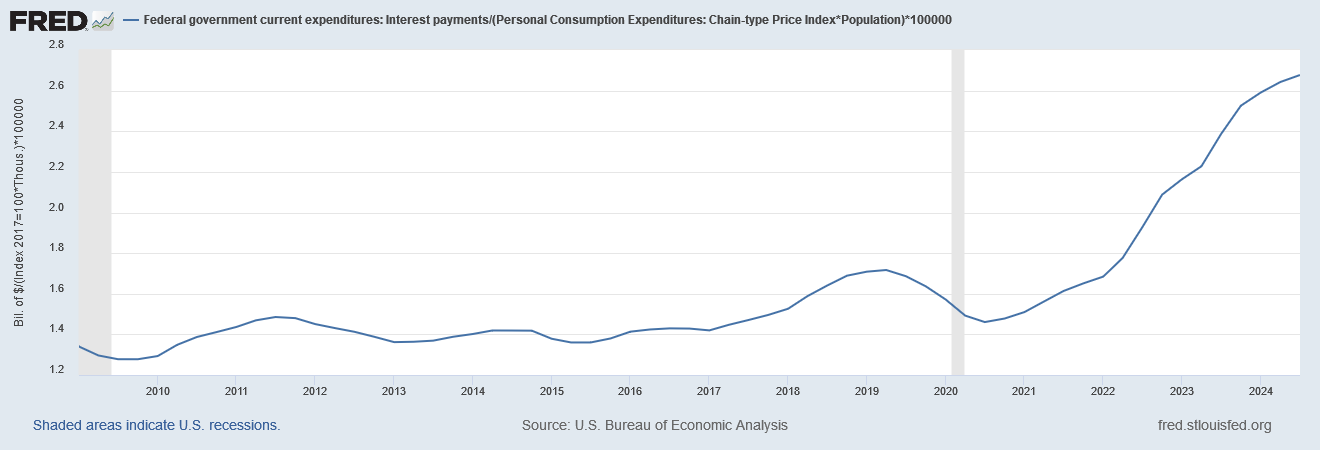

The federal old-age programs, Social Security and Medicare, are going bust. The latest trustees reports show the Social Security trust fund running out of money in 10 years and the Medicare hospital insurance trust fund running out in 11. With federal debt growing even as a share of GDP, and interest on that debt rising, Congress has shown every indication of being willing to drive us off the cliff. The federal government is now paying over $10,000 per person every year on interest alone (Figure 1).

Most likely, Congress will end up raising taxes rather than cutting benefits for retirees, a politically powerful constituency. But what if instead of putting all our eggs in the basket of fixing Congress, we used our state governments to get out from under the federal fiscal yoke?

State governments should negotiate directly with the federal government for exemptions from failing federal programs — and the taxes that pay for them. Then states could choose what to do about these programs for their own citizens. Replacing federal with state programs would give us more rational policies and allow for beneficial innovation and experimentation.

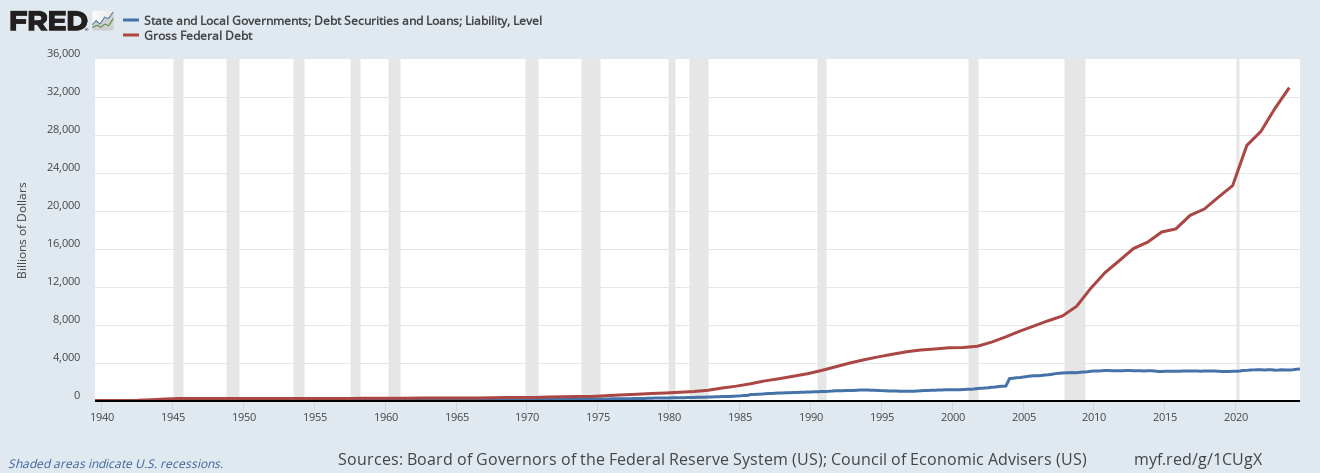

State legislatures are far nimbler and more fiscally responsible than Congress, in part because they can’t run big deficits and don’t have access to the central bank. State and local debt is a small fraction of federal debt (Figure 2).

Big-government states might want to continue Social Security and Medicare as large, costly, pay-go systems, but they would still have the incentive and the means to reform these programs for fiscal solvency.

Small-government states would probably enact free-market reforms. Some might shrink the pay-go portion of these programs while supplementing them with compulsory savings like defined-contribution retirement plans and “health status insurance” that keeps premiums from private health insurance plans reasonable even as you age (rather like the way life insurance premiums don’t rise with age if you buy them when you’re young). Other states might shrink these programs by means testing them for future retirees, so that middle-income and wealthy retirees aren’t living off the taxpayer. Eventually, some states may choose to end these programs altogether, perhaps by floating bonds to pay back what everyone has contributed, converting an open-ended future liability into a fixed, present liability.

You could even make it so that any state that opts out of Social Security and Medicare contributes to the solvency of the system. Older states that will probably have a disproportionate number of beneficiaries in the future will contribute to the solvency of the system simply by opting out. Younger states that are contributing more to these programs could be required to pay the net present value of their future expected contributions net of benefits as a condition of getting their exemptions.

It might seem weird to have some states covered by some federal programs and others not at all. But there’s nothing unconstitutional or legally problematic about it. There would be a rule of law problem if Congress targeted specific states for benefits. For example, when Congress was negotiating Obamacare, they briefly added a “Cornhusker kickback” that would have offered special Medicaid subsidies to Nebraska, and only Nebraska. That was clear favoritism, and it might even have been illegal. But there’s no favoritism involved in letting one state run its own old-age programs, so long as the federal government doesn’t subsidize that choice.

In fact, that’s just how it works in Canada. The Canada Pension Plan (CPP) is a public retirement program for Canadians, funded out of a payroll tax on all workers. Provinces have the right to opt out of the CPP, and Quebec has done so, running its own Quebec Pension Plan.

Federations around the world have proven fully capable of offering different levels of autonomy to their regions, based on what those regions want. This arrangement is often called “asymmetric autonomy.” Besides Canada, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom are other rich democracies where regions have different powers.

If, say, New Hampshire wanted to get out of Social Security and Medicare, how would they go about it? It’s pretty straightforward. Congress could pass a law exempting New Hampshire residents from contributing to these programs and receiving benefits from them, while ordering the Social Security Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to turn over records to the state relating to contributions and benefits for state residents and requiring states to maintain data-sharing with these agencies to guarantee seamless benefits for people who move in or out of state. The law could build in a two- or three-year transition period to allow the state time to build its own administration for taking in revenues and disbursing benefits.

Workers moving between opt-out states and the rest of the country could retain their contribution and benefit histories. For example, a state might calculate benefits based on combined work history across the two systems, but only apply its own benefit rules for the portion earned within the state. A worker who spends 25 years in an opt-out state and 15 years contributing to Social Security could receive prorated benefits from both systems.

Once one state does it, other states will likely want to follow suit. So Congress could set up a procedure for states to qualify to run their own programs, rather than issuing state by state exemptions.

There’s no reason why this process should be limited to just Social Security and Medicare. States already have the ability to set up their own occupational safety and health systems, for example. The law just needs to be amended to exempt these states from federal regulation. In Canada, the provinces are responsible for securities regulation, whereas in the US, both states and the federal government regulate securities, causing inefficient duplication. States should be allowed to withdraw from the purview of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Skeptics might claim that giving states too much autonomy will let them impose costs on the rest of the country. First of all, negotiated exemptions could be carefully designed to prevent these costs. But second, these skeptics need to tell us why, if these costs are so debilitating to commerce, international commerce has flourished without a world government to run transfer programs, labor regulation, financial regulation, and so on.

Letting states opt out of federal programs might seem radical. But current programs often have rules allowing partial opt-outs. Not every state has the same Medicaid eligibility rules, for example. When Vermont authorized a single-payer healthcare program, the state would have sought a waiver of PPACA (Obamacare) rules. (The state abandoned the plan when the taxes required to fund single-payer turned out to be too high.)

George Mason University law professor FH Buckley is the most notable advocate of far-reaching state opt-outs from federal programs. In his book American Secession, he frames the idea as a compromise alternative to outright secession from a fiscally irresponsible government.

The federal government is becoming increasingly unmanageable, costly, and even dangerous to our prosperity. State governments could press Congress now for the right to take over programs that the federal government has failed to manage properly. Congress won’t give up power unless it becomes politically costly for them to keep it.